THE CAMPAIGN OF 1824

James Monroe’s two terms in office as president of the United States (1817–1825) are often called the “Era of Good Feelings.” The country appeared to have entered a period of strength, unity of purpose, and one-party government with the end of the War of 1812 and the decay and eventual disappearance of Federalism in the wake of Alexander Hamilton’s death.

Thomas Jefferson, living his final years in retirement at Monticello, might well have taken satisfaction in 1824 at the total dominance of Republicanism, or the Democratic-Republican Party, in American political life. Every major candidate for public office designated himself a Republican and derided factionalism. But the “good feelings” were illusory. Beneath the veneer of unity seethed a bubbling cauldron of factionalism and political rivalry that, in the upcoming presidential election, would put the less-than-fifty-year-old United States to a severe test.

This was a transitional period in American politics, made evident in the selection of presidential candidates in 1824. No system for nominating candidates had developed. The caucus system was in decline as the electorate grew, and essentially any party or group could nominate a candidate for the presidency. Some candidates, such as Andrew Jackson, were nominated almost simultaneously by different groups in different places. Nor was there anything like today’s presidential campaigns. Candidates did not tramp the countryside giving speeches or offer well-defined platforms. More often they sparred through the press or through local supporters.

Campaigning by press and proxy encouraged the politics of insinuation and slander. Journalists and political cronies could trumpet the most scurrilous accusations against their opponents while the candidates themselves stood serenely above the dirty fray. Forged documents and outrageous rumors were disseminated to destroy reputations; reports even hit the press in 1824 that John Quincy Adams, one of the major candidates, didn’t wear underclothes and went to church barefoot! The focus on personalities did not, however, wholly obscure issues of substance. Candidates, voters, and electors all had serious views on issues such as government spending and corruption in public life.

As politicians and their supporters jockeyed for position in 1824, four major candidates for the presidency came to the fore. Of them, none craved victory more than Henry Clay (1777–1852). Born in Virginia but now hailing from Kentucky, where he rivaled Andrew Jackson for the role of “candidate of the West,” Clay had served since 1811 as Speaker of the House of Representatives. But he had no intention of stopping there. Though Clay had failed to displace his rival John Quincy Adams as Monroe’s secretary of state, the office that was traditionally regarded as the last step before the presidency, he determined to run for president in 1824. Clay advocated what he called the “American System,” an economic policy of internal improvements for transportation and agriculture funded by taxation; a protectionist tariff on behalf of American industry; and preservation of a national bank.

Andrew Jackson (1767–1845) competed with Clay for support in the West, but lacked his opponent’s political experience. Jackson had served briefly as a judge, governor of the Florida Territory, and member of the House of Representatives, and was in 1824 a US senator; but his public service had been undistinguished on the whole. Feisty and charismatic, he attracted supporters as a military hero and supposed advocate of the common man, but repelled others who regarded him as an ignorant frontiersman and opportunist who sought dictatorial power. Both supporters and detractors could agree on one thing: Jackson had a vicious temper, and woe to the man who crossed him. Although he lacked a well-defined political platform—he supported a somewhat more moderate version of Clay’s American System—Jackson garnered wide support in Pennsylvania and in the South and West.

William H. Crawford of Georgia (1772–1834) represented a small group known as Old Republicans or Radicals. Passionate advocates of states’ rights who considered themselves true Jeffersonians, the Radicals strongly distrusted the central government and argued for limited budgets and against protective tariffs. They were therefore violently opposed to Clay’s American System. Despite his hardline platform, Crawford usually was affable and easygoing enough, although he sometimes betrayed a temper every bit as violent as Jackson’s. While secretary of the Treasury under Monroe, Crawford had reputedly brandished his cane angrily at the President, who had responded by snatching up a pair of fire tongs and driving Crawford out of the White House. He was popular in Congress despite his reputation for being politically unscrupulous. Unfortunately, Crawford had suffered a debilitating stroke in September 1823, and his attending physicians then brought him to death’s door by bleeding him mercilessly. Despite his physical weakness, Crawford refused to abandon his candidacy.

On paper, no candidate was more qualified for the presidency than John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts (1767–1848). Son of the second president of the United States, Adams had studied at Harvard and served under James Madison as US minister to Russia. After his recall in 1814, he played a major role in crafting and negotiating the Treaty of Ghent, which ended the War of 1812. Adams had reached his political pinnacle as secretary of state under Monroe, helping to shape the Monroe Doctrine, and he seemed destined for the presidency.

Adams lacked only one ingredient for success: charisma. Bald, short, and rotund (despite being an avid swimmer), he felt most comfortable among books and struck others as dour and stand-offish. Among intellectuals or when inspired by a topic of interest—such as slavery, which he firmly opposed—Adams sometimes let down his guard; and when he had imbibed enough wine, he became positively loquacious. A part of him always yearned to leave politics and become a professor or professional man of letters, but his strong sense of duty held him back. A workaholic, Adams took pride in devoting himself thoroughly to his public duties.

The Adams platform closely approximated Clay’s American System, with its spending on internal improvements and a tariff. Adams tried to stay aloof from partisan politics, though, believing that his record of service should be sufficient inducement for votes. Above all, Adams loathed the gutter tactics employed by his opponents and their supporters. Like George Washington, he felt it beneath him to angle openly for office. Adams responded to frustrated supporters of his candidacy by quoting a line from Shakespeare’s Macbeth: “If chance will have me king, why, chance may crown me, / Without my stir.” All of which is not to say that Adams lacked ambition: his pursuit of the presidency was driven by his desire to live up to the family name; a semi-Messianic feeling that he was a man of destiny who could benefit mankind; and a genuine fear of what would happen to the country if any of his detested opponents won the presidency.

There was no single election day in 1824. Instead, votes accumulated through the autumn as voters cast ballots for individuals or slates of electors who typically pledged to support a certain candidate in the Electoral College. In six states—Delaware, Georgia, Louisiana, New York, South Carolina, and Vermont—legislatures chose the electors, while elsewhere they were chosen by popular vote. Some electors were not even pledged to a specific candidate, while others were pledged but subsequently changed their minds.

The results of the voting exposed the fragmented nature of American politics despite the appearance of unity and heralded a full-fledged political crisis. Among the four major candidates, Jackson won 99 electoral and 152,901 popular votes; Adams won 84 electoral and 114,023 popular votes; Crawford won 41 electoral and 46,979 popular votes; and poor Henry Clay trailed the field with 37 electoral votes even though he had received 47,217 popular votes. Since none of the four held an actual majority, by the terms of the Twelfth Amendment to the Constitution, the House of Representatives would have to choose among the three candidates with the most electoral votes: Jackson, Adams, and Crawford.

The results were especially galling to Clay, since by a narrow margin he had missed having a chance at election through the House of Representatives, where his enormous influence as Speaker might have made the difference. Even so, he remained in an important position—not quite as kingmaker, but still having a critical role in swaying the balance of power. Another man in a position of influence was John C. Calhoun of South Carolina (1782–1850), who served as secretary of war under Monroe. Calhoun had originally sought the presidency, but when his candidacy failed to gain traction he entered the race for vice president and won easily (unlike today, that office was filled by separate election).

Calhoun hesitated. He did not feel entirely comfortable with either Jackson or Adams; but on the other hand, he and Crawford absolutely loathed each other. Crawford’s Radicals suspected that Calhoun was a secret Jackson man, however; and that alone was sufficient to convince them not to support the colorful Tennessean and guarantee his victory as they might otherwise have done. Instead, the Radicals decided to hold out against both Jackson and Adams in what they expected to be a protracted balloting process in the House of Representatives. In preventing either of the two main candidates from winning, they hoped to force the House to choose Crawford as a third option.

A period of furious lobbying and canvassing for votes gripped the House during the autumn and early winter of 1824–1825 as state representatives measured the candidates. Meanwhile the Marquis de Lafayette, hero of the Revolutionary War, embarked on his tour of the United States and brought a nostalgic tone to Washington politics. Lafayette and Jackson entered into a genial and public correspondence that benefited the Tennessean’s standing. In the public eye, Jackson absorbed some of the Frenchman’s aura of Revolutionary heroism, setting him further apart from the cynical Crawford and the dyspeptic Adams.

On January 8, 1825, Clay, as a member of the House, transformed the character of the debate by officially throwing his support behind Adams despite nonbinding instructions from the Kentucky legislature to back Jackson. Clay announced his decision publicly two weeks later. The declaration was not unexpected and was easily justifiable in terms of policy. Adams and Clay agreed on the fundamentals of the American System, to which Crawford was unalterably opposed. Clay also thought Crawford’s physical debility should preclude him from the presidency. And while Clay did not lack regard for Jackson, he thought Old Hickory insufficiently experienced for such high public office. Moreover, since Clay and Jackson competed for support in the West, a combination with Adams seemed more calculated to vault Clay, in 1828 or 1832, into the presidential office he craved. Rumors flew, however, that Adams had made some underhanded deal to secure Clay’s support. If Adams won, his subsequent treatment of Clay would be closely watched.

Snow blanketed Washington on February 9, 1825, as the House of Representatives convened to choose the president for the first time since 1801. Up to the last moment delegates scurried back and forth across the chambers for hurried conferences, and Clay had to call for order as the polling began. Each state then cast a ballot that was determined by its delegation, with a majority of ballots being required for election.

There were several important “battleground states.” Daniel Webster of Massachusetts (1782–1852) played a vital role in bringing Maryland over to Adams; and Clay helped to entice Kentucky, Ohio, and Louisiana away from Jackson and to the secretary of state. Missouri’s vote, determined by a single delegate, was essentially bought for Adams, who promised to maintain the delegate’s brother in judicial office. No state was more important than New York, however, where the delegates remained deadlocked between Adams and Crawford. One man, Stephen Van Rensselaer, held the balance that would turn the vote either way, and he nearly broke down under the pressure of making his decision. Deeply religious, Van Rensselaer bowed his head to pray and, upon looking up, saw a ballot for Adams lying on the floor before him. That evidently made up his mind—or so the story went—and with New York in the Adams camp the final piece fell into place.

On the first and only ballot, Adams won a clear majority of thirteen states against seven for Jackson and four for Crawford. The Radicals’ hopes of preventing a quick decision thus failed disastrously while Jackson, who had seemed to hold the inside track after winning the popular majority, found himself empty-handed. Learning of his son’s election, old John Adams sent him a note invoking “the blessing of God Almighty” on his presidency.

Jackson at first accepted the news of John Quincy Adams’s election with good grace, and even greeted the incoming president cordially at a reception given by Monroe on the night of the election. Unfortunately for Adams, it all went downhill from there. His decision to appoint Clay secretary of state seemed to confirm rumors that the two men had struck a deal, and cries of a “corrupt bargain” flew around the country. Jackson, meanwhile, returned to Tennessee but grew increasingly convinced that he had been cheated. Proclaiming that “the Judas of the West [Clay] has closed the contract and will receive the thirty pieces of silver,” Jackson declared his undying enmity to the new regime.

Instead of seeking allies, the stubborn Adams only incited the growing political combination against him by refusing to conciliate Crawford and his Radicals, pushing immediately for an aggressive program of public works that drove them into the Jackson camp. Calhoun and his followers likewise aligned themselves with Jackson. In a twinkling, Adams found himself surrounded by an increasingly well-organized political party determined to obstruct his policies and make him a one-term president. Clay would later rue his decision to accept the secretary of state’s office as political suicide, for he never again came within a sniff of the presidency.

John Quincy Adams’s victory in the election of 1824 would turn to bitter gall. Subject to savage political attacks and blocked at every turn by an obstructionist Congress and vindictive political enemies, he grew increasingly bitter as his presidency stagnated. He sought reelection in 1828 out of sheer stubbornness, but fully expected and even looked forward to losing to Jackson—which he did. Adams’s subsequent career as a Massachusetts delegate in the House of Representatives would be serene compared to the ordeal of the election of 1824 and its aftermath.

Source: Edward G. Lengel. "Adams v. Jackson: The Election of 1824." History Now: The Journal of the Gilder Lehrman Institute. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Accessed May 22, 2016. http://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/age-jackson/essays/adams-v-jackson-election-1824

Anonymous. c. 1824. "Campaign Token for Andrew Jackson." Brass coin. The Virginia Historical Society. http://www.vahistorical.org/collections-and-resources/virginia-history-explorer/getting-message-out-presidential-campaign-0

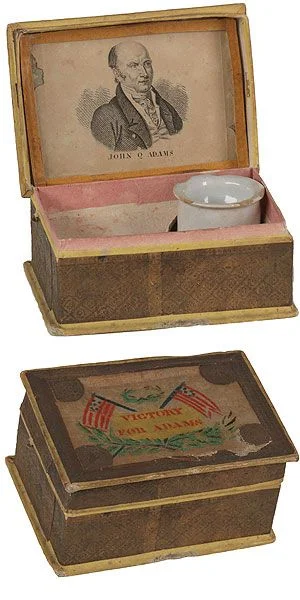

Anonymous. c.1824. "Victory for Adams." Sewing Box. Virginia Historical Society.

James Akin. 1824. "Caucus curs in full yell, or a war whoop, to saddle on the people, a pappoose president." Etching with Aquatint and Engraving. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540