THE CAMPAIGN OF 1900

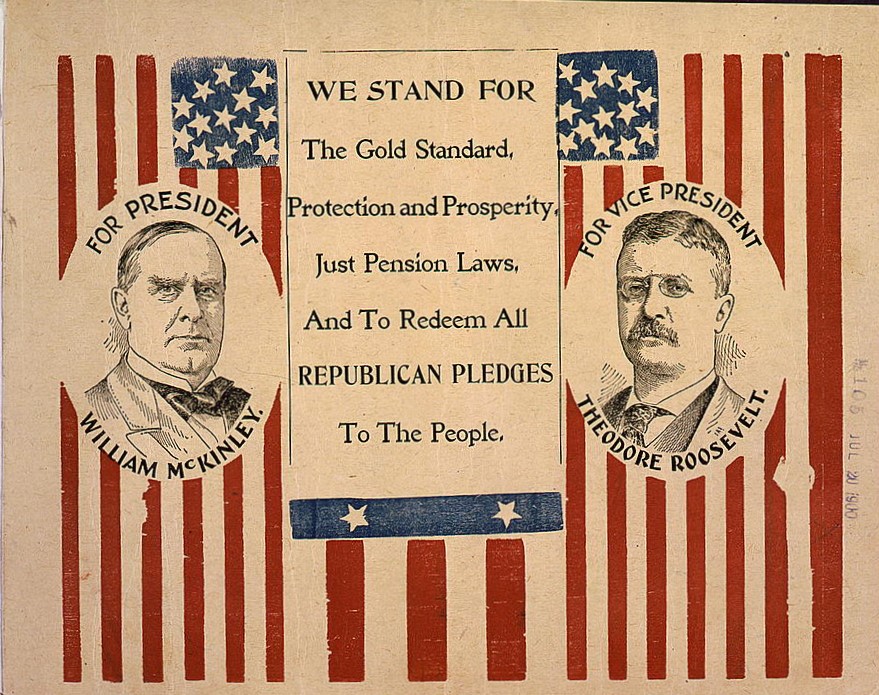

After four years in office, McKinley's popularity had risen because of his image as the victorious commander-in-chief of the Spanish-American War (see Foreign Affairs section) and because of the nation's general return to economic prosperity. Hence, he was easily renominated in 1900 as the Republican candidate. The most momentous event at the Philadelphia convention centered on the vice presidential nomination of Governor Theodore Roosevelt of New York. Vice President Garret A. Hobart of New Jersey had died in office, and Roosevelt's candidacy added a popular war hero and reform governor to the ticket. Setting up the stage for a rematch of the 1896 election, the Democrats again nominated Bryan at their convention in Kansas City. Grover Cleveland's former vice president, Adlai E. Stevenson, took the second spot on the Democratic slate.

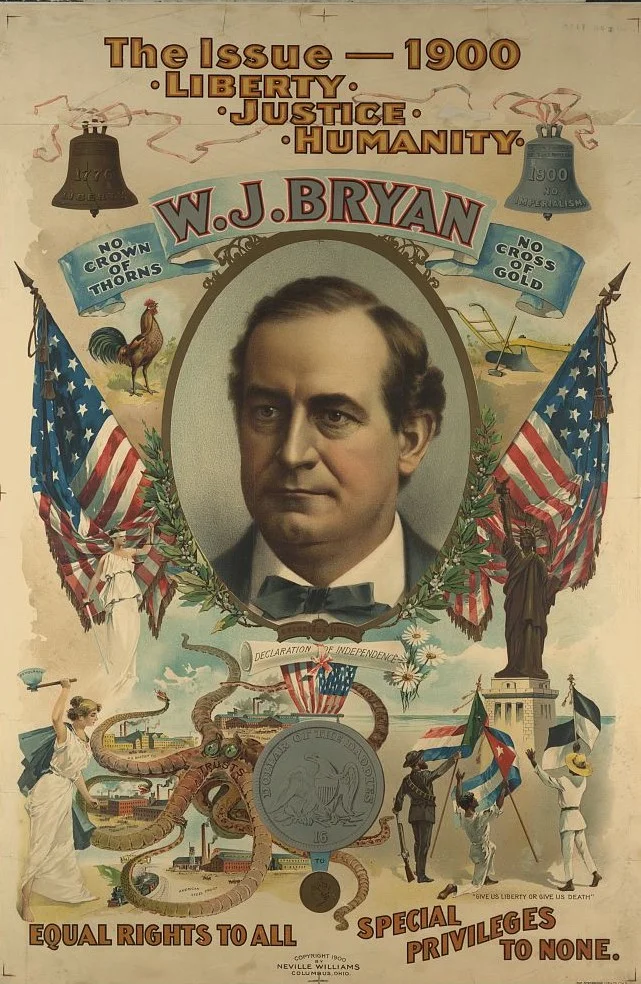

The rematch played to old and new issues. Bryan refused to back off his call for free silver even though the recent discoveries of gold in Alaska and South Africa had inflated the world's money supply and increased world prices. As a result, the U.S. farming industry saw its profits grow as crops such as corn commanded more money on the market. Farmer dissatisfaction was less than it was in 1896, and gold was the reason behind it. Hence, Bryan's silver plank was a nonissue to the farming community, which was one of his main constituent groups. Responding to these voter sentiments, Democratic Party managers included the silver plank in their platform but placed greater emphasis on expansionism and protectionism as the key issues in the election. The Democrats also opposed McKinley's war against Philippine insurgents and the emergence of an American empire, viewing the latter as contrary to the basic character of the nation. The Republicans countered with a spirited defense of America's interests in foreign markets. They advocated expanding ties with China, a protectorate status for the Philippines, and an antitrust policy that condemned monopolies while approving the "honest cooperation of capital to meet new business conditions" in foreign markets.

Duplicating the campaign tactics of 1896, the Republicans spent several million dollars on 125 million campaign documents, including 21 million postcards and 2 million written inserts that were distributed to over 5,000 newspapers weekly. They also employed 600 speakers and poll watchers. As in 1896, McKinley stayed at home dispensing carefully written speeches. His running mate, Theodore Roosevelt, campaigned across the nation, condemning Bryan as a dangerous threat to America's prosperity and status.

Although not a landslide shift comparable to election swings in the twentieth century, McKinley's victory ended the pattern of close popular margins that had characterized elections since the Civil War. McKinley received 7,218,491 votes (51.7 percent) to Bryan's 6,356,734 votes (45.5 percent)—a gain for the Republicans of 114,000 votes over their total in 1896. McKinley received nearly twice as many electoral votes as Bryan did. In congressional elections that year, Republicans held fifty-five Senate seats to the Democrats' thirty-one, and McKinley's party captured 197 House seats compared to the Democrats' 151. Indeed, the Republican Party had become the majority political party in the nation.

Source: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. “William McKinley: Campaigns and Elections.” Accessed May 23, 2016. http://millercenter.org/president/biography/mckinley-campaigns-and-elections.

Neville Williams. 1900. "The Issue – 1900. Liberty. Justice. Humanity. W.J. Bryan." Neville Wiliams. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540

Anonymous. 1900. "We Stand for the Gold Standard." Lithograph. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540