THE CAMPAIGN OF 1928

When the Republican convention in Kansas City began in the summer of 1928, the fifty-three-year-old Herbert Hoover was on the verge of winning his party's nomination for President. He had won primaries in California, Oregon, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Michigan, and Maryland. Among important Republican constituencies, he had the support of women, progressives, internationalists, the new business elite, and corporate interests. Party regulars grudgingly supported Hoover, but they neither liked nor trusted him. Hoover's nomination was assured when he received the endorsement of Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon, who controlled Pennsylvania's delegates.

The convention nominated Hoover on the first ballot, teaming him with Senate Majority Leader Charles Curtis of Kansas. The Republican platform promised continued prosperity with lower taxes, a protective tariff, opposition to farm subsidies, the creation of a new farm agency to assist cooperative marketing associations, and the vigorous enforcement of Prohibition. The party also proclaimed its commitment to delivering a "technocrat" known for his humanitarianism and efficiency to the White House. In his acceptance speech, Hoover promised "a final triumph over poverty"—words that would soon come to haunt him.

The four-term New York governor, Alfred E. Smith, a Catholic opponent of Prohibition (the common term for the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution that banned the manufacture, sale, or transport of liquor), won the Democratic nomination on the first ballot. His "Protestant Prohibitionist" running mate, Senator Joseph G. Robinson of Arkansas, balanced Smith's "Wet (anti-prohibitionist) Catholic" stance. Democrats hoped that Smith could unify the party and defeat Hoover, something that few political pundits at the time considered even remotely possible. The Smith-Robinson ticket actually mirrored the divide in the party between southern, Protestant backers of Prohibition and northern, urban, often Catholic opponents of Prohibition. The Democratic platform downplayed the tariff issue and emphasized the party's support for public works projects, a federal farm program, and federal aid to education. It also promised to enforce the nation's laws, a nod to supporters of Prohibition who worried that Smith might try to repeal the Eighteenth Amendment.

Hoover ran a risk-free campaign, making only seven well-crafted radio speeches to the nation; he never even mentioned Al Smith by name. The Republicans portrayed Hoover as an efficient engineer in an era of technology, as a successful self-made man, as a skilled administrator in a new corporate world of international markets, and as a careful businessman with a vision for economic growth that would, in the words of one GOP campaign circular, put "a chicken in every pot and a car in every garage." Republicans also reminded Americans of Hoover's humanitarian work during World War I and in the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927. Hoover the administrator, the humanitarian, and the engineer were all on display in the 1928 campaign film ï"Master of Emergencies," which often left its audiences awestruck and in tears. But perhaps Hoover's greatest advantage in 1928 was his association with the preceding two Republican administrations and their legacy of economic success.

Religion and Prohibition quickly emerged as the most volatile and energizing issues in the campaign. No Catholic had ever been elected President, a by-product of the long history of American anti-Catholic sentiment. Vicious rumors and openly hateful anti-Catholic rhetoric hit Smith hard and often in the months leading up to election day. Numerous Protestant preachers in rural areas delivered Sunday sermons warning their flocks that a vote for Smith was a vote for the Devil. Anti-Smith literature, distributed by the resurgent Ku Klux Klan (KKK), claimed that President Smith would take orders from the Pope, declare all Protestant children illegitimate, annul Protestant marriages, and establish Catholicism as the nation's official religion. When Smith addressed a massive rally in Oklahoma City on the subject of religious intolerance, fiery KKK crosses burned around the stadium and a hostile crowd jeered him as he spoke. The next evening, thousands filled the same stadium to hear an anti-Smith speech entitled, "Al Smith and the Forces of Hell."A consistent critic of Prohibition as governor of New York, Smith took a stance on the Eighteenth Amendment that was politically dangerous both nationally and within the party. While the Democratic platform downplayed the issue, Smith brought it to the fore by telling Democrats at the convention that he wanted "fundamental changes" in Prohibition legislation; shortly thereafter, Smith called openly for Prohibition's repeal, angering Southern Democrats. At the same time, the Anti-Saloon League, the Women's Christian Temperance Union, and other supporters of the temperance movement exploited Smith's anti-Prohibition politics, dubbing him "Al-coholic" Smith, spreading rumors about his own addiction to drink, and linking him with moral decline. A popular radio preacher put Smith in the same camp as "card playing, cocktail drinking, poodle dogs, divorces, novels, stuffy rooms, dancing, evolution, Clarence Darrow, nude art, prize-fighting, actors, greyhound racing, and modernism."The Republicans swept the election in November. Hoover carried forty states, including Smith's New York, all the border states, and five traditionally Democratic states in the South. The popular vote gave a whopping 21,391,993 votes (58.2 percent) to Hoover compared to 15,016,169 votes (40.9 percent) to Smith. The electoral college tally was even more lopsided, 444 to 87. With 13 million more people voting in 1928 (57 percent of the electorate) than had turned out in 1924 (49 percent of the electorate), Smith won twice the number of voters who had supported the 1924 losing Democratic candidate, John W. Davis. Hoover, though, also made significant gains, tallying nearly 6 million more Republican votes than Coolidge had four years earlier. Smith's Catholicism and opposition to Prohibition hurt him, but the more decisive factor was that Hoover ran as the candidate of prosperity and economic growth.

Source: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. “Herbert Hoover: Campaigns and Elections.” Accessed May 23, 2016. http://millercenter.org/president/biography/hoover-campaigns-and-elections.

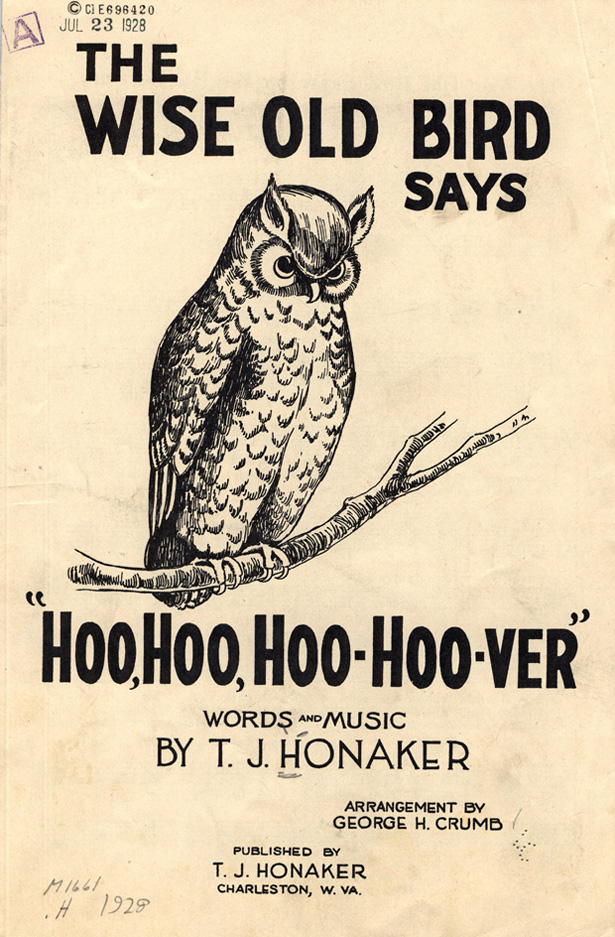

Anonymous. 1928. "Hoo, Hoo, Hoo - Hoover." T.J. Honaker. Printed Book Cover.

Anonymous. 1928. "For President - Alfred E. Smith - Honest - Able - Fearless." Morgan Lithograph Co. Photolithograph. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540