THE CAMPAIGN OF 1932

Political observers in the early 1930s were of decidedly mixed opinion about the possible presidential candidacy of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Many leaders of the Democratic Party saw in Roosevelt an attractive mixture of experience (as governor of New York and as a former vice presidential candidate) and appeal (the Roosevelt name itself, which immediately associated FDR with his remote cousin, former President Theodore Roosevelt.)FDR's record as governor of New York—and specifically his laudable, if initially conservative, efforts to combat the effects of the depression in his own state—only reinforced his place as the leading Democratic contender for the 1932 presidential nomination. Under the watchful eyes of his political advisers Louis Howe and James Farley, FDR patiently garnered support from Democrats around the country, but especially in the South and the West. In preparation for his presidential bid, Roosevelt consulted a group of college professors, dubbed the "Brains Trust" (later shortened to the "Brain Trust"), for policy advice.

Other observers, however, were not so sanguine about his abilities or chances. Walter Lippmann, the dean of political commentators and a shaper of public opinion, observed acidly of Roosevelt: "He is a pleasant man who, without any important qualifications for the office, would very much like to be president." FDR's Democratic Party, moreover, was both factionalized and ideologically splintered. Several other candidates sought the nomination, including Speaker of the House John Nance Garner of Texas (who found support in the west) and the party's 1928 candidate, Alfred Smith (who ran strong in the urban northeast). The party further split on two key social issues: Catholicism and prohibition. Smith was a Catholic and wanted to end prohibition, which pleased Democrats in the Northeast, but angered those in the South and West.

In 1932, though, the key issue was the Great Depression, not Catholicism or prohibition, which gave Democrats a great opportunity to take the White House back from the Republicans. While FDR did not enter the Democratic convention in Chicago with the necessary two-thirds of the delegates, he managed to secure them after promising Garner the vice-presidential nomination. FDR then broke with tradition and flew to Chicago by airplane to accept the nomination in person, promising delegates "a new deal for the American people." FDR's decision to go to Chicago was politically necessary: he needed to demonstrate to the country that even though his body had been ravaged by polio, he was robust, strong, and energetic.

Roosevelt's campaign for president was necessarily cautious. His opponent, President Herbert Hoover, was so unpopular that FDR's main strategy was not to commit any gaffes that might take the public's attention away from Hoover's inadequacies and the nation's troubles. FDR traveled around the country attacking Hoover and promising better days ahead, but often without referring to any specific programs or policies. Roosevelt was so genial—and his prescriptions for the country so bland—that some commentators questioned his capabilities and his grasp of the serious challenges confronting the United States.

On occasion, though, FDR hinted at the shape of the New Deal to come. FDR told Americans that only by working together could the nation overcome the economic crisis, a sharp contrast to Hoover's paeans to American individualism in the face of the depression. In a speech in San Francisco, FDR outlined the expansive role that the federal government should play in resuscitating the economy, in easing the burden of the suffering, and in insuring that all Americans had an opportunity to lead successful and rewarding lives.

The outcome of the 1932 presidential contest between Roosevelt and Hoover was never greatly in doubt. Dispirited Americans swept the fifty-year-old FDR into office in a landslide in both the popular and electoral college votes. Voters also extended their approval of FDR to his party, giving Democrats substantial majorities in both houses of Congress. These congressional majorities would prove vital in Roosevelt's first year in office.

Source: Source: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. “Franklin D. Roosevelt: Campaigns and Elections.” Accessed May August 11, 2016. http://millercenter.org/president/biography/fdroosevelt-campaigns-and-elections

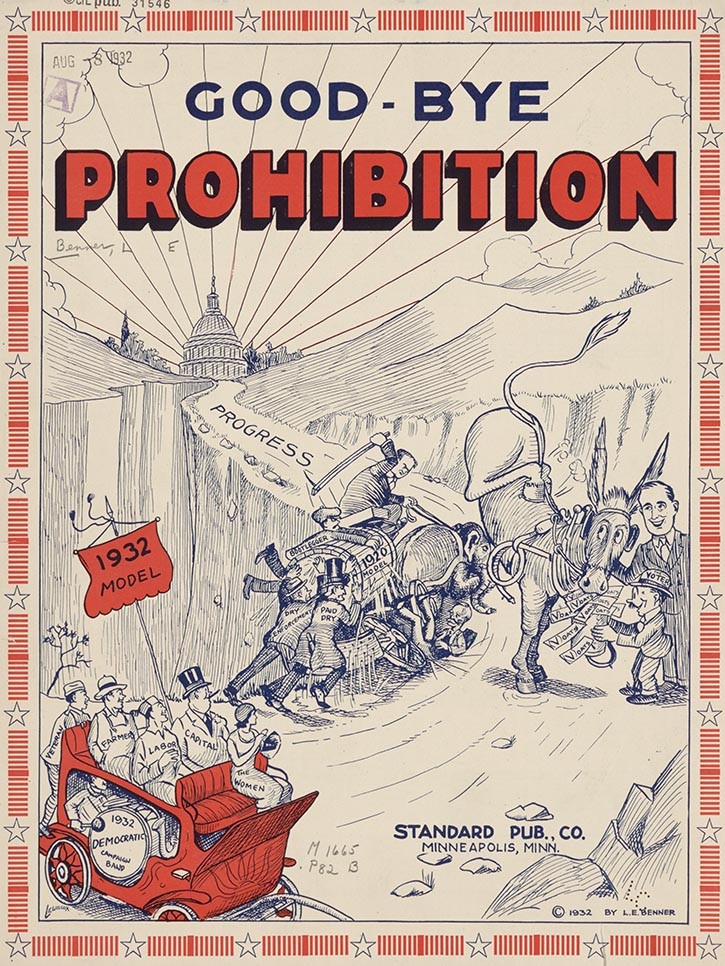

Artist Illegible. 1932. "Good-Bye Prohibition." Good-Bye Prohibition. Cover for Book of Music. L.E. Benner, Music & Words. Standard Pub., Co. Library of Congress.

Anonymous. 1928. "This is a Hoover House." The Women’s Committee for Hoover. Printed sign. George Fox University Digital Commons. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/hoover_images/57/