THE CAMPAIGN OF 1944

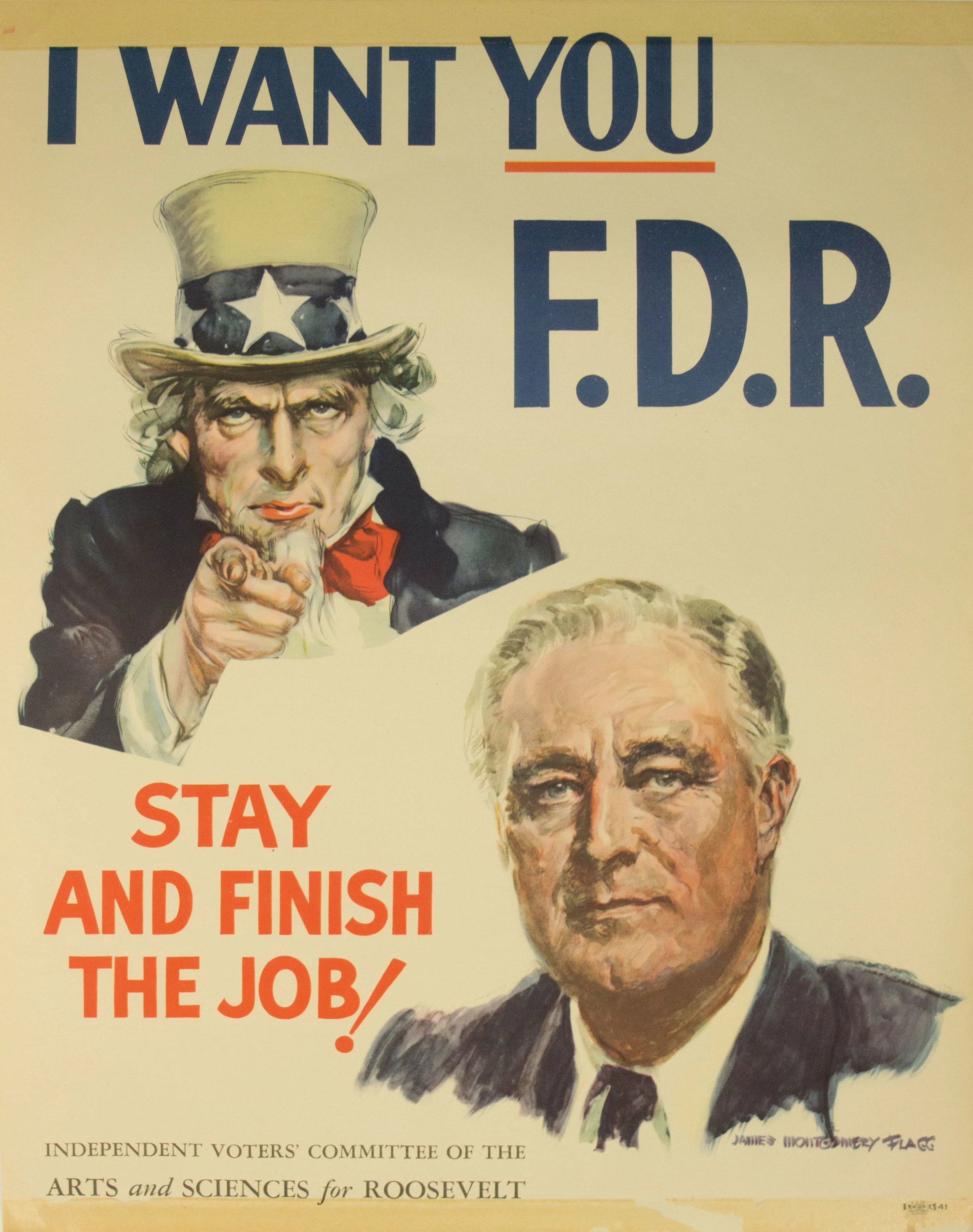

When President Franklin Delano Roosevelt decided to seek a fourth term in 1944, his campaign would come to mark a major moment in the history of presidential elections for several reasons. No president had run for a fourth term prior to Roosevelt and FDR remains the only person to have been elected to a fourth term, or in fact, a third term. It was only the third time in US history up to then that a presidential election had taken place in wartime. The election was also momentous because Roosevelt was seriously ill, and he and his aides orchestrated a cover-up that hid his failing health from the American people.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can see how consequential the 1944 election was. FDR’s victory would lead to the passage in 1951 of the Twenty-second Amendment to the Constitution barring presidents from serving more than two full terms. His physical condition at the time of his victory virtually ensured that his vice president would become president, and when FDR died three months into his fourth term, Harry Truman helped launch the nuclear age when he dropped two atomic bombs on Japan to end the war in the Pacific. The Cold War with the Soviet Union also began on Truman’s watch. The 1944 presidential election inaugurated a politics of prosperity that would last for decades, while FDR’s deception about his health helped pave the way for the now-familiar custom in which candidates are forced to release results of their physicals, disclose income taxes, and reveal at least some details of their personal lives to the public.

FDR defended his precedent-breaking decision to seek a fourth term on several grounds. In late 1944, Roosevelt reflected that while he “hate[d] the fourth term . . . and the third term as well,” he thought he was able to “plead extenuating circumstances!” He believed, he explained, that Americans deserved to have the chance “freely to express themselves every four years.” Unlike some of his contemporaries, Roosevelt claimed, he did not feel the need to cling to power just for the sake of holding power. “I would, quite honestly, have retired to Hyde Park with infinite pleasure in 1941” had it not been for the international crisis. He felt ethically bound to break from tradition in 1940 and, again, in 1944; he described the possible election of his 1940 opponent, Republican Wendell Willkie, as “a rather dangerous experiment,” as he had little foreign policy experience and was not the man to handle an international emergency. By 1944, with America in its third year of the war, FDR considered it his obligation to remain in office until Hitler had been defeated.

Roosevelt faced re-election challenges on a variety of thorny fronts. Democratic bosses regarded Vice President Henry Wallace as a left-wing ultra-liberal, and they refused to accept him on the 1944 ticket. FDR was forced to dump Wallace, and he browbeat Missouri’s Senator Harry Truman into running as his number two. Truman had won praise for leading a Senate Committee investigation that turned up billions of dollars in fraud and government waste in the war effort, but he had only modest experience with foreign affairs.

An even greater problem for the President was that his body was falling apart. As only a handful of doctors and members of his inner circle knew, FDR had had hypertension in the early 1940s. High blood pressure had led to congestive heart failure by the time his re-election campaign rolled around. According to the author and medical doctor Hugh E. Evans, by March 1944 FDR was clearly suffering from heart failure. His death—due to a brain hemorrhage on April 12, 1945—was “predictable,” Evans has argued.

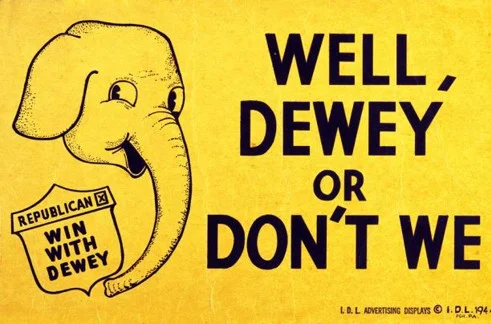

Roosevelt faced a more formidable Republican opponent in 1944 than he had in 1940. New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey defeated Wendell Willkie, a utility executive who had been the 1940 Republican nominee, for the GOP’s 1944 nomination. Willkie had crisscrossed Wisconsin in the hopes of winning enough delegates in its April 4 primary to propel him toward the 1944 nomination. Yet Willkie failed to take a single delegate from the state’s primary, and he ended his bid on that disappointing note. Some Republican conservatives flirted with drafting General Douglas MacArthur into the race. But the MacArthur boomlet fizzled after letters he had written to one of his supporters were made public, which, among other things, highlighted the general’s disdain for civilian authority.

Dewey was prim, exact, and at times incendiary. He was a one-time district attorney of New York County who had also sought the Republican presidential nomination in 1940.[7] During a June 1940 rally in front of 2,000 people in Burlington, Vermont, he had blasted the Roosevelt administration for failing to staunch the internal threat that communists posed to Americans. “The least we can demand of our national government is that it stop coddling men and women whose major objective is the destruction of American institutions,” Dewey huffed. “The administration is . . . riddled with communists and fellow travelers.”

In 1944, Dewey continued his anti-communist chest-thumping. He sought to sow doubts about FDR’s physical health and questioned his capacity to defend America from domestic enemies lurking in the shadows. But he failed to mount a significant challenge to Roosevelt’s New Deal program, stepping on conservatives’ own argument when he said in September that if elected he would “keep” the New Deal, “maybe [even] add to it some.” The charges that FDR was soft on communism failed to resonate with the public. Moreover, Dewey was one of the icier presidential candidates of his era—a sharp contrast to FDR’s radiant warmth. Dewey was, one liberal writer said, “intelligent without depth, shrewd without vision, jocular without humor. . . . [Even] his friends don’t like him.” “Pompous and cold,” journalist David Brinkley sniffed, as author David M. Jordan has pointed out.

If Dewey’s candidacy was hyperbolic and if his personality was remote, Roosevelt was no longer the sterling campaigner of the 1930s. The President had lost his vigor. His face was haggard and gaunt; his clothes hung loose around his frame; his hands trembled so much that Truman once saw him unable to make his own coffee. FDR’s physician, Ross McIntire, and a coterie of aides managed a cover-up that hid FDR’s illnesses from the voting public. Roosevelt’s use of radio helped him overcome doubts about his wherewithal to handle a fourth term. When he was preparing to oversee a military exercise at San Diego’s Camp Pendleton in July 1944, he had a seizure. This happened just as the Democratic National Convention was taking place. Still, Roosevelt delivered his acceptance speech to the convention over the radio. Only a handful of his closest aides knew about his seizure. Another key moment in the campaign came when FDR addressed the Teamsters on September 23, 1944. His talk, which was carried over the radio, rebutted Republican-led smears that the President had ordered the use of a Navy destroyer to rescue his Scottish terrier, Fala, from an island where the dog allegedly had been stranded.

“These Republican leaders have not been content with attacks on me, or my wife, or on my sons,” FDR said in his speech. “No, not content with that, they now include my little dog, Fala. Well, of course, I don’t resent attacks, and my family doesn’t resent attacks, but Fala does resent them.” His humor disarmed his critics and tamped down rumors that the President was unfit to serve four more years. His spirited speech was a bracing reminder of his vigor and his mastery of the airwaves. Whereas television would have made FDR’s deceptions impossible, the radio enabled him to use his voice to cover up the severity of his physical deterioration.

Most importantly, two issues—peace and prosperity—framed the election and explain why FDR won an unprecedented fourth term. On the eve of the 1942 mid-term elections, Roosevelt confronted economic troubles at home and military challenges abroad. While his name was not on the ballot that year, the returns on Election Day were a bad omen for FDR. His party lost forty-seven House seats and seven Senate seats. Beginning in 1943, Congress began to eliminate some of Roosevelt’s cherished New Deal programs such as the Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Youth Administration. The nation’s mood was less than ebullient. The economy had frustrated consumers on the home front; World War II seemed to be stalemated.

By Election Day 1944, however, the Allies had pulled off D-Day and liberated Paris. In his Pulitzer-winning synthesis Freedom from Fear: The American People in World War II, historian David Kennedy points out that news from the front lines was positive in 1944. “Shortly before election day, the navy defeated the Japanese in the war’s last great sea duel at Leyte Gulf, MacArthur histrionically waded ashore in the Philippines, and the first US troops entered Germany.” Nearly three years after the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Americans concluded that victory in World War II was now achievable.

Equally vital to FDR’s chances, the US economy had risen from its years-long doldrums and had started an expansion that would endure for decades to come. The US national income had expanded by more than $40 billion between 1942 and 1944. More Americans began to see and feel the rewards of this boom. Wartime production of tanks, planes, bombs, and guns—and the millions of jobs created by the war economy—augured a peacetime economy of unlimited potential. After years of economic sacrifice and stagnation, a kind of economic Promised Land seemed within the nation’s grasp. FDR managed to give Americans hope that he had put the country on a glide path to economic victory.

Not even FDR knew what he would do in a fourth term. He sought to leave as many options open as possible; his intentions were contradictory and, ultimately, inscrutable. During a news conference on December 28, 1943, FDR told reporters that his single-minded economic focus had been replaced by his wartime agenda. He talked in metaphors, explaining that when he took power in 1933 the United States was “an awfully sick patient” with “grave internal” wounds. FDR had to don his “Dr. New Deal” persona—prescribing the remedies that prevented the patient from dying. But then he said that when this patient “was in a pretty bad smashup” on December 7, 1941, Dr. New Deal was forced to bring in his partner, “Dr. Win-the-War, to take care of this fellow who had been in this bad accident.” Dr. Win-the-War was now in charge of saving the country.

FDR contradicted his news conference when he declared in his January 11, 1944, State of the Union address that “the one supreme objective for the future . . . can be summed up in one word: Security. And that means not only physical security which provides safety from attacks by aggressors. It means also economic security, social security, moral security.” Perhaps Dr. New Deal was making a comeback? He went on to outline an economic bill of rights that would give every American “regardless of station, race, or creed” access to enough food, a good job, “a decent home,” and “adequate medical care.” “All of these rights spell security. And after this war is won we must be prepared to move forward, in the implementation of these rights, to new goals of human happiness and well-being.”

The anti–New Deal Congress rejected almost all of Roosevelt’s economic bill of rights, but that did not harm his re-election bid. The President had at least one major legislative victory in 1944—the GI Bill of Rights (or the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act), which he signed into law in June. The act provided returning veterans with access to college loans, help with buying homes, job training, and other services that enabled them to pursue the American Dream as they returned home. The law won support from Republicans and Democrats and veterans, and it symbolized FDR’s nationwide effort to honor soldiers’ military sacrifices and harness the lever of government intervention to spur individual initiative to build a better, more prosperous postwar world.

In the face of these successes Dewey had a hard sell. Despite the hardships that the war had imposed on the American people, FDR was commander in chief and seemed more than up to the task of winning it. He was also steering the economy with a sure hand. Roosevelt had quelled concerns in his own ranks with his selection of Truman. The Washington Post faulted Dewey for having failed to confront head-on “the great issues of war and peace” at stake in 1944. Dewey lacked the expertise and “conviction” to lead World War II America. The electorate was ultimately reluctant to cast aside the incumbent commander in chief, who seemed best equipped to achieve a military victory and transition the country to a sound future.

In the end, FDR defeated Dewey by more than three and a half million votes, winning a 333-vote margin in the Electoral College.[19] Franklin Delano Roosevelt would be dead by April, but the election’s ramifications reverberate into the twenty-first century. Roosevelt’s deception about his health was one factor moving the political culture to a place where candidates would be forced to disclose intimate details of their lives. Wartime presidents, FDR’s victory suggested, had an electoral advantage while running for re-election—so long as their leadership seemed to be paying dividends. His fourth-term win also resulted in the amendment that has barred presidents from winning more than two elections—perhaps depriving Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton of third terms. Last, Roosevelt’s victory, and Truman’s ascension, helped ensure that the New Deal would continue to define Americans’ relationship with their government—that with his re-election Roosevelt’s vision of humanizing the industrial economy had become an accepted aspect of Americans’ lives, so vital to the country’s future that even FDR’s 1944 opponent vowed to “keep” it.

Source: Matthew Dallek. 2012. "Franklin Delano Roosevelt—Four-Term President—and the Election of 1944." History Now: Journal of the Gilder Lehrman Institute. Accessed: May 24, 2016. http://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/world-war-ii/essays/franklin-delano-roosevelt%E2%80%94four-term-president%E2%80%94and-election-1944

Anonymous. 1944. "Well, Dewey or Don’t We; Republican; Win With Dewey." IDL Advertising Displays. Screen Print. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540

James Montgomery Flagg. 1944. "I Want You FDR – Stay and Finish the Job!" Chromolithograph. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540